One man’s journey through, and back to, hospice

By: Craig Dresang, CEO of YoloCares

It was a hot muggy Midwestern July when I left my home in Chicago to spend the weekend with my parents in northern Wisconsin. 90 degrees and 90 percent humidity. The air was thick with the smell of pine, birch, and fresh rain. Lightning from passing thunderstorms flashed in the distance.

Once home, my mom was hell-bent on taking a bicycle ride with me. She was not able to bike around the entire lake like we usually did, but it did not matter. I knew she simply needed to feel like she could soar again on that plum-colored Schwinn.

After we peddled back home from a short excursion along the west shore of Shawano Lake, mom ordered pizza. When we sat down with our pepperoni and cheese, she opened a bottle of wine and began to tell me that her treatments weren’t working so well anymore.

I was nine when mom received her first cancer diagnosis 20 years earlier. It was breast cancer. Both she and her best friend, Mrs. Eggabean, received the same diagnosis during the same week, from the same doctor. Six months later, Mrs. Eggabean was dead, but mom was somehow alive.

She was hairless, bloated, breastless and, I imagine, terrified. But it never showed. She was hopelessly hopeful. Aggressive treatment gave her nearly two more decades of life. But about halfway through her “bonus years” as she called them, she told me that when she was younger she bargained with God; if she could live long enough to see her children become adults, then she would accept whatever fate would deliver.

That fate played out on a bone-chilling, Northwoods winter day when her doctor used the word, “terminal.” Her prognosis: six months. Still, her optimism, coupled with a measure of denial and new chemotherapies bought her an additional two years. When treatments stopped working, the doctor said she could have a shunt put into her chest and wear an experimental chemo-pack strapped to her waist. “That will never happen,” she told me. “I will never have a shunt put in. No more treatments. No hospitals. I just want to be home.”

So I was surprised when my dad called eight weeks later to say that he took mom in for a check-up and the doctor checked her into the hospital. Dad didn’t even know why she was admitted.

Shortly after our conversation, I jumped into my little yellow Honda and drove four hours north. When I arrived at the hospital and entered my mom’s room she immediately sprung up in bed like a jack-in-the-box with a giant smile and said, “I’ve been waiting for you, you old moose!” Yes, “Old Moose” was a term of endearment that my mother lovingly called me for years.

Suddenly, a visible tsunami of panic, confusion and sadness washed away her smile. She started to cry like I have never seen her cry before. Then, she pulled open her gown to show me the shunt they put into her chest. “Look what they did to me!” she cried.

I struggled to find out what was happening. Even though I was practically living at the hospital, it took three days and a come-to-Jesus meeting with the hospital president to finally pin down the doctor and force him to have a conversation with me and my family. He said, “Your mom is going to be fine. She’ll be going home by next Tuesday. This state of confusion she is in is temporary.” When the doctor left the room, the nurse pulled me aside and said, “I can’t tell you this because I could lose my job, but you need to call the rest of your family. Your mom is dying.”

What followed was a week of mom laying in a hospital bed transitioning into a coma and being pumped full of chemo-therapy until the day she died. It was cold, sterile, meaningless and not what she or any of us wanted for her. It was clear that her care was not aligned with her values, with her wishes, or with who she was.

She, and we, were robbed of any sense of dignity, choice, compassion, or clarity around what was happening. It was not, and still is not, fair. There must be a better way.

——————————————————————————

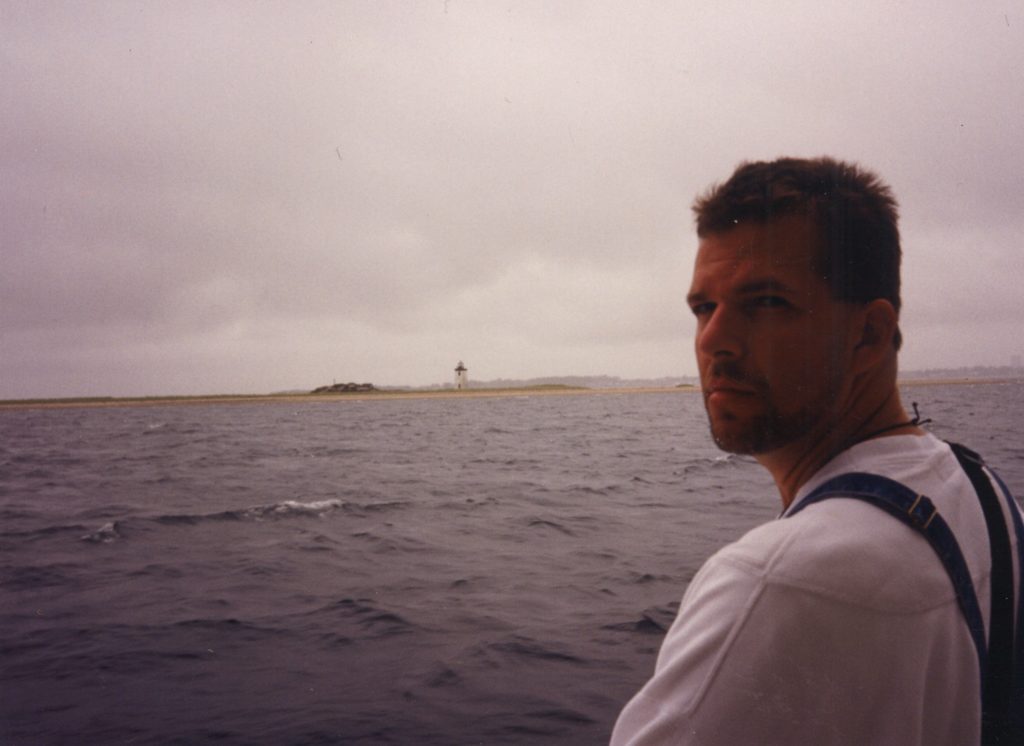

After mom’s death, I was determined to not let this same thing happen to my life-partner Dan if his lymphoma ever became untreatable. Like my mom, he would be facing months of chemotherapy and radiation. Dan and my mom were my best friends, they were my source of strength and the two people who always believed that I could do anything in this world that I put my mind to. In very different ways, they were the two people on this great big planet who got me.

Dan was a house painter who came from a tightly knit Irish-German Catholic family of ten kids, who all lived, as we did, in or near Oak Park, home of Hemingway, Frank Lloyd Wright and Betty White. The area had a healthy supply of giant old houses for Dan to keep himself and a few crewmen busy.

He was masculine with a beefy frame, sandy blonde hair, and a perfect smirky charming smile that was often accompanied with laughter. When he was being intense or loving, it was as if his laser-focused pupils could see directly into my soul. He was at once strong and gentle.

Eighteen months after my mom passed, I was back in Oak Park, snuggled in bed beside Dan.

It was June. The turquoise clematis and tangerine-colored roses outside our kitchen window were in full bloom. The sun, warm and gorgeous, fell through our old bedroom windows onto the foot of the bed where our cat, Tia, was curled in a ball at Dan’s feet.

When I woke up, I saw that Dan was awake too. He was lying still with his eyes wide open and a look of terror on his face. He said, “I can’t breathe! I feel like I’m suffocating. I can’t breathe!” I called his doctor right away. After I told her what was happening she said, “Remember Craig? We talked about this. If you bring Dan back to Northwestern, he won’t be coming back home. But I can have a hospice team there shortly to take care of him at your house. You both said you wanted that right?” I paused. “I guess I just wasn’t expecting this, but yes, that’s right . . . that is what we want,” I said.

Though it felt like days, a hospice team showed up within a few hours. Almost immediately, they got Dan’s breathing under control. Clearly, he was more comfortable and at ease. Was it the oxygen, the morphine, the compassionate energy of a caring team? Whatever it was, it was working. He was better.

Later the next week, I returned to my job for a few days. I was in a meeting when I got a call from Dan’s nurse. She said, “It’s time to come home.”

“Did he die?” I screeched. I could not stand the thought of not being with him in his final hours, of not letting him sense my presence. “No, no,” she said. “But it won’t be long. Maybe just a day or so. He’s most worried about you. He needs to know that you’re going to be okay. You need to assure him. And, tell him that you’ll miss him too.”

I rushed home, wondering how I could say anything without dissolving into a lake of despair. Halfway home, I pulled my car into a Home Depot parking lot to cry, and then to write down the things I wanted to say to Dan.

The hardest thing about terminal illness is watching the person you love disappear bit by bit by bit. It happens slowly at first, and you think things will get back to normal, but they never do. Long before Dan’s final weeks, I was already grieving. He was still here, but not fully.

So, alone in a deserted parking lot and in between sobs, I decided to write a poem to describe the things I would miss. I read it to Dan that evening. It’s called YOU.

You make antiquity an intimate and wondrous place

A candlelit sanctuary illuminated with a mosaic of rubies and sapphires

Midnight table talk about the Creator

Fearless swims in frigid Lake Michigan waters

Spells of warm and generous laughter

Purple stain-making love-making beneath a Mulberry tree

Lounging between flannel sheets from daybreak to dinner

Being charmed by snowflakes as they fall thick on branches of spruce and maple

Ten-gallon kettles of ox-tail stew

Painted pine window sills accessorized with pink potted orchids

Exquisite gestures of affection that if recorded would fill parchment from here to where you soon will be

You inspire me

To dream big

To believe that I can

To carry on

The bravery to choose things of joy – the stuff that makes six-year-olds happy – comes from you

Even now, you remind me that simple pleasures are life’s real thrills

Poetry slams at the Green Mill Tavern

Ice cream trucks, rollerblading on new pavement

Soaring skyward on the swings at New Buffalo Beach

Skipping work when the sun burns warm against a cloudless sky

Grandmothers who cherish gin and late-night conversation

And, the unconditional love of a mom

When you’re gone, I will reach for you

Hoping that you’ve returned to your side of the bed

I will still love you with everything in me

I will crave you…. smell you

And continue to be changed by you.

What we thought would be a few final days evolved into a few poignant weeks. Some days were better than others. Dan’s mom, nine siblings, their spouses, countless nieces and nephews, aunts and uncles, neighbors and friends were in and out of our house every day, surrounding Dan with affection, stories, Joni Mitchell music, laughter, final farewells, and prayers. Our house had become a treasure chest of meaning and everything important.

One day when he was feeling unusually well, he was hungry for fried chicken. With help from his family, we whipped up the best chicken dinner this side of Paula Deen. We had a bedside picnic in our room. His giant rectangular oxygen machine became a picnic table with a red and white checked tablecloth, a bottle of red wine, steaming sweet corn, foothills of mashed potatoes, and crunchy mac and cheese. Mary Chapin Carpenter and Van Morrison played softly in the background. This brief window of time together was perfect . . . stunning really!

After Dan’s first bite of chicken, he sat straight up in bed with a smile I had not seen in months and with rays of appreciation and love beaming from his eyes he declared: “This is the best damn chicken I have ever had.”

A few days later, Dan’s sister Marion and I were lying in bed with him, just talking, stroking his head, when we noticed him staring, eyes wide open, into the corner of the room. He raised his arm and pointed. “There are ANGELS in here. Do you see them?” Marion and I looked at each other. “No, Danny, we don’t see them.”

“They’re right there!” he told us. When we didn’t respond he repeated himself, “I’m not hallucinating. They are right there.” His sister asked, “What do they look like?” He said, “They’re beautiful. There are three of them. The one in the middle has her arms open to hug me, the other two are just standing there.” His eyes were glued to the corner of the room and the look on his face was a union of fascination and profound peace. Marion and I locked eyes, knowing that he, and we, were in the presence of the Divine.

The next day when I told his nurse about it, inquiring to see if the experience could be related to morphine or the process of his body shutting down. She said, “Oh no, honey. What he saw is real. It happens all the time.”

The morning that Dan died, I was in bed by his side, holding his hand, his fingers woven through mine. At five o’clock in the morning something strange happened. I woke up. I never wake up at five, and back then every day was so exhausting, I could barely get up by nine.

But I was awake and something prompted me to open my eyes . . . and when I did I saw that Dan had taken the oxygen tube out of his nose and gently placed it on his chest as if to say, “I no longer need this.” His body was still warm, but he was gone.

I believe that I woke up at the very second his spirit left his body. My senses were temporarily heightened so that I would feel this transition and wake up at this precise and very special moment.

These were the gifts that hospice gave to Dan, to me, to his family. The gifts of clarity and knowing the truth, the gifts of love and dignity, and the realization that no matter the circumstance, every minute, every single second of life matters and is meaningful.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but my relationship with Dan and our shared experience, changed the trajectory of my life and my career. It is what drew me into hospice as a vocation and it is why I do what I do today.

——————————————————————————

Craig Dresang is CEO of YoloCares, an affiliate of the California Hospice Network, and a columnist for the Davis Enterprise. He is also a panelist for the California Arts Council and a member of the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation.

Janet Osterdock

Thank you Craig for sharing your life and thoughts with end-of-life care. Dennis and I are grateful for your work and leadership in our community. You make the world a better place and we’re thankful.

daoud

Thank You Craig!

I work for a marketing company (Saba Seo) – one of our clients is Home Care Assistance – and I stumbled across Yolo while doing my monthly search terms report.

I decided to read your story and was deeply touched. I don’t why I’m writing to you accept to connect and offer appreciation and gratitude.

Thank you for bringing peace of mind to so many worried and struggling folks out there and for your deep profound spiritual share.

Sending you much joy, light and blessings!

Godbless

Craig

Thank you so much . . . in many ways we are all on the same journey.