Damn straight I’m confident

By: Craig Dresang, CEO, YoloCares

A Pride Month special column

Over the years, co-workers and colleagues have occasionally said to me, with an element of shock, “You are certainly confident.” In nearly every instance, the comment was meant neither as a compliment nor a criticism. Rather, it was simply an observation rooted in a sense of surprise or amazement. Sometimes, these verbalized observations have felt more like a judgement on my character . . . an insinuation that I have no right to be confident. In other words, I should know my place.

It usually leaves me wondering why people feel the need to point out my confidence the way they would point out a rare species of fish in an aquarium or a run-away zebra that escaped the zoo. My professional reputation, over a span of three decades, has been one of getting results, and of being open-minded, collaborative, and the opposite of authoritarian. So why is my ability to possess confidence such a wonder?

When I dug a little deeper with a close colleague about the nature of his comment to me, he said, “The world is not used to confident gay leaders in certain industries or professions.” Gay men are expected to be confident in areas like the arts, beauty, social services, or the food industry. He continued, “But how often do people see confident gay leaders in banking, business, manufacturing, or tech?” I was grateful for his candor, but completely shocked.

From presidential candidates to corporate billionaires, society has made clear that a sense of confidence is not just acceptable, but expected and celebrated from straight men in circles of power . . . even if they are completely incompetent or immoral. But hold the phone if a gay man exhibits the same level of confidence for being competent or exhibiting integrity.

Confidence was not easy to come by for me or for many others in the LGBTQ community. I grew up in a time and place that required me to be inconspicuous. Many of the Wisconsin communities where my family lived were more than 95 percent white, and by all appearances, zero percent LGBTQ.

Confidence was not easy to come by for me or for many others in the LGBTQ community. I grew up in a time and place that required me to be inconspicuous. Many of the Wisconsin communities where my family lived were more than 95 percent white, and by all appearances, zero percent LGBTQ.

This was an era when no one in either my high school or university graduating class was openly gay. Men fit into a certain stereotype. They were football fanatics (Greenbay Packers fans), sports nuts, and beer drinkers. They hunted, chewed tobacco, drove oversized pickups, farted on each other, and worked hard. They carried enormous confidence in who they were and in what they did for a living. They had pride.

It was a time when identifying as LGBTQ could easily get you injured or killed. At the least, it would certainly mean you would be ridiculed and made to feel small and insignificant. When I was in middle school, being bullied was an everyday occurrence. It was only 26 years ago that Matthew Wayne Shepard, a gay student at the University of Wyoming, was beaten, tortured and left to die in Laramie, WY because of his sexual orientation.

A 95-year-old friend of mine from New York once told me that when he was in his 20s, it was illegal for two men in a bar to be dancing together or hugging. “Back then,” he said, “New York gay bars were named after birds like flamingo, eagle, or parrot, so they could be easily identified by the gay community.” There was always a lookout person, like a bouncer, at the entrance who would watch for the police. When he saw an officer heading down the street, he would shut off the lights inside the bar, and then turn them back on. “That way, if men were dancing together, they knew to stop and separate themselves when the lights went off. Then, when the lights came back on, they were just standing around having conversations like they would in a straight bar.” He continued, “If they were caught dancing together, they would be arrested.”

The journey toward pride for gay men in my generation has been hard-won. When half of my friends were sick and dying of AIDS in the 1980s and 90s, no one seemed to mind. Over one million deaths later, the federal government — including the president of the United States — could not care less. At a very young age, out of necessity and without any training or support, I learned how to be a perpetual caregiver, healthcare navigator, and case manager.

On the work front, sexual orientation has been used to deny many of us opportunities for career advancement, promotions or equal pay. In 1994, I asked my employer why a candidate with much less experience, expertise, and responsibility than me was earning 50 percent more. He said, “Because he is married and starting a family. You don’t need to earn as much.” Another employer once advised me to lay low regarding my sexual orientation and suggested that I go into conversion therapy to change who I am.

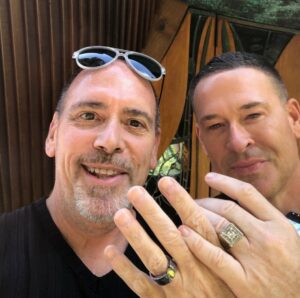

Even here in Davis, not that long ago, an employment attorney insisted on referring to my husband of 20 years as my paramour. Not partner. Not husband. Not significant other. But paramour, which means an illicit or scandalous partner of a married person. There could not be a more demeaning and prejudiced term used to describe our relationship. Ironically, the law firm says it specializes in litigating discrimination claims related to sexual orientation.

So now, if someone comments on my sense of confidence or pride, I will simply smile and agree. That confidence is the product of survival and experience. Our tribe has emerged from a world that wanted us to stay hidden and ashamed of how we were created.

We now live in a time when our community needs to hold onto and expand its confidence (when and where it is justified) and take pride in how far we have come. The rights and freedoms that took generations to realize should not be taken for granted. This is our time to be heard and seen. Our journey is far from over.

Judy Heberle

Wonderful article! Kudos!

Gwendolyn Kaltoft

Thank you Craig ~ with Much Love ~ Gwendolyn